Hidden in Plain Sight – Staff Exposure to Suicide and Responses to a New, Systemic Model of Workplace Postvention

Alison Clements, Priscilla Ennals, Susan Young, and Karl Andriessen

Published: 11 December 2024

ABSTRACT

Background: Exposure to suicide is associated with a range of psychosocial harms which Australian employers have a legislated responsibility to mitigate. Aims: Examine the impact of suicide on staff, current workplace responses and the efficacy of a new, systemic model of workplace postvention. Method: Interviews and focus groups with 54 staff in 22 workplaces from the commercial, government, and not-for-profit sectors. Results: Every participant had experienced the suicide of a client or colleague and reported a range of short- and long-term negative impacts, including suicidal ideation. This contrasted with the overall lack of workplace postvention, which increased the risks of psychosocial harms to staff. The new model was effective in tailoring a systemic approach to workplace postvention. Limitations: The small size of the sample limits generalisability; however, the prevalence of exposure to suicide and lack of workplace preparedness were strikingly consistent. Conclusion: The impact of suicide on staff is significant and current workplace responses are ineffective and potentially harmful. The new model improves staff and workplace preparedness through tailored and co-designed training, governance and supports.

The economic costs of mental ill health and suicide in Australia have been estimated at between $150 and 220 billion per annum (Australian Government Productivity Commission, 2020). In a workplace context, it has been estimated that mental ill health costs between $15.8 and 17.4 billion per annum (The Australia Institute & Centre of Future Work et al., 2021).

Since 2021, the Australian Government has invested over $300m in a multifaceted, public health approach to suicide prevention (Bambridge & McLean, 2023). This is based on calls for a coordinated and integrated approach across governments and communities, including increasing workforce capacity to recognize and respond to suicidal distress (National Suicide Prevention Adviser, 2020). Exposure to suicide is also a public health problem with about half of the Australian population estimated to have known someone who has died in this manner (Pirkis et al., 2019). People exposed to suicide are vulnerable to a range of psychosocial harms including depression, attempted suicide, and death by suicide (Andriessen, Rahman et al., 2017; Cerel et al., 2016; Pitman et al., 2016). Staff working With clients vulnerable to suicide or who are part of a workforce with a higher rate of suicide (e.g., males, Aboriginal, and Torres Strait Islanders) are at increased risk of these psychosocial harms. Australian legislation (Work Health and Safety Act 2011, 2023) requires that workplaces mitigate psychosocial harms including traumatic events such as the suicide of a client or colleague and job demands such as working with populations vulnerable to suicide.

Table 1. Baseline questionnaire results (n = 67).

Suicide postvention describes planned and coordinated responses to mitigate the risk of further harm and facilitate recovery following suicide (Andriessen, 2009). Grad (2005) recommended a systemic approach to the impact of suicide targeting the individual, group/family, and society. In a workplace context, Molnar et al. (2017) noted the value of a public health approach to identify, mitigate, monitor, and evaluate the risk of vicarious trauma in the workplace.

A recent case study (Clements, 2022) explored the impacts of suicide on workplaces, using the example of a funeral company. Results published in 2022 (Clements tt al. 2022) revealed common staff challenges with emotions, communication, and engagement when working with families bereaved by suicide. Organizational barriers and opportunities to prepare and support staff were also identified and discussed.

The case study proposed a new systemic model of workplace postvention informed by the lived experience of staff and tailored to workplace context and capacity, to increase organizational preparedness and improve outcomes for staff and their clients. The model employs a collaborative approach to risk identification, co-design of tailored training, and postvention governance, together with development of integrated referral and support pathways tailored to workplace capacity and needs.

The model informed a 2023 pilot project called Suicide Aware undertaken by Neami National, an Australian community mental health organisation, in four workplaces from the community, government, and commercial sectors in Perth, Western Australia. This qualitative study was conducted to examine the efficacy of the model via the four workplace projects and to further explore the impacts of suicide and current workplace responses.

Methods

Sampling and Recruitment

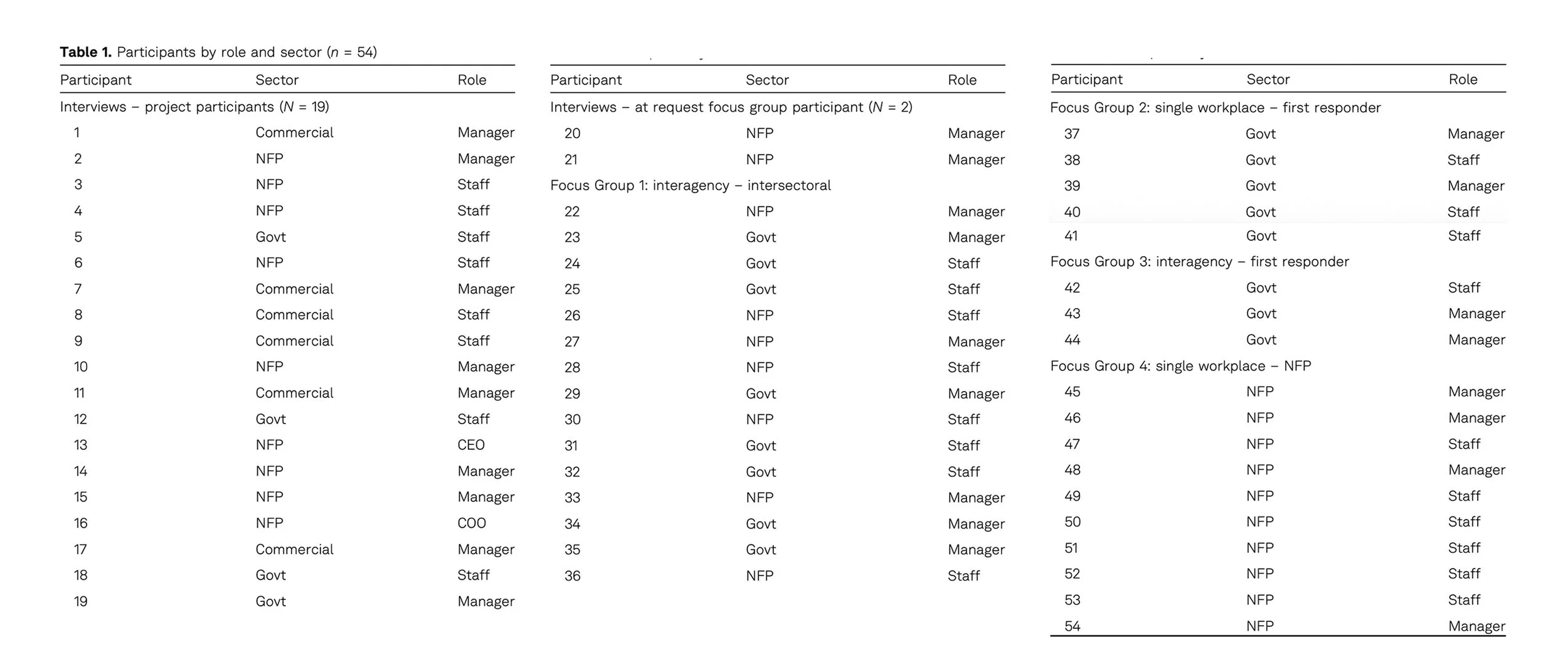

We recruited managers and staff from human services agencies, including health, financial counseling, education, homelessness, child and youth support, mental health, funeral providers, legal advice, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community support, and first responders, from the government, not-for-profit, and commercial sectors, and invited them to attend either interviews or focus groups (see Table 1 for a deidentified list of participants by role and sector).

The target number for recruitment was originally limited to the four workplaces undertaking the projects and 10 other agencies. This was extended during recruitment due to the large number of participants electing to attend focus groups. The final sample was 54 staff in service delivery, work health and safety, and managerial roles from 22 workplaces. The sizes of the workplaces ranged from 110 staff to over 57,000 staff.

Most of the agencies in the study cohort were familiar with Neami National through interagency networks. Four agencies were recruited specifically because of their participation in the projects. The remaining 18 agencies were selected because the nature of their services exposed them to populations vulnerable to suicide or people bereaved by suicide. Recruitment was via direct email from the research team and all workplaces were in the Perth metropolitan area. Participants received information and consent forms confirming that data would be deidentified including staff and workplace names. The purpose and scope of the study was summarized, and it was reiterated that participation was voluntary. Participants were offered access to the data and the option to withdraw at any stage of the study.

Interviews and focus groups were used to gather complementary sources of data. Individual interviews concentrated on personal experiences with suicide and workplace responses following suicide, and focus groups shared collective experiences and reflections. To further enrich the data, deidentified interviewee experiences were shared with focus group participants for discussion. The use of multiple methods in qualitative work has been shown to be effective when researching sensitive subjects (Guest et al., 2017).

Researcher Clements conducted 21 interviews and four focus groups together with one or more of the four-person researcher team, based on their availability. Except for one interview, at least two researchers were present at each interview and focus group. Nineteen of the 21 interviewees were project participants (six commercial sector interviewees, four government sector interviewees, and nine not-for-profit sector interviewees) and two were focus group invitees from the not-for-profit sector who elected to interview. There was one interagency, intersectoral focus group (seven not-for-profit sector participants and eight government sector participants, one single-agency first responder focus group (five government sector participants), one interagency first responder focus group (three government sector participants), and one single not-for-profit workplace focus group (10 participants).

Data Collection

Semistructured interviews and focus group protocols permitted flexible discussion of the research questions, prompting follow-up questions exploring specific and common issues and themes. Interviews ranged from 45 to 80 minutes and focus groups from 90 to 120 minutes. The average interview time was 55 minutes and the average focus group 100 minutes. Information was not collected on the demographics of the decedent or time since death as the focus of the study was on impact and response.

Interview questions included: How might your staff/workplace be exposed to suicide? How might this impact staff/managers and the workplace? How would you describe the impact on you and others? What processes are in place to support postvention in your workplace? What works well? Are there any gaps? What do you think might improve postvention in your workplace?

Additional questions to project participants included: How were you involved in the project? How would you describe the process? Were there any notable outcomes? What improvements could you suggest to the approach?

Focus group questions included: Have you or your colleagues experienced suicide in the course of your work? What have you noticed about the impact – on yourself, colleagues, and/or the workplace? What is in place now to support staff? What might improve workplace awareness and responses to mitigate the impact of working with suicide?

Discussions were recorded using either Microsoft Teams or an audio recording device and manually transcribed. Researchers checked transcripts for accuracy.

Analysis

The research team adopted a narrative thematic approach drawing from the conversational interviewing and focus group process (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009). Researchers attending each interview and focus group discussed responses immediately following, and these reflections were shared in fortnightly meetings of the research team. Each team member reviewed each interview and focus group transcript several times, making notes on important points, how these addressed the research questions or provided new information, and questions arising. The researchers discussed emergent characteristics and tensions in the data, and this iterative process was continued through the presentation of deidentified findings for discussion in focus groups.

Data were categorized into Xmind (computer software), according to the research questions, i.e., staff exposure and impacts, workplace responses, responses to trials, and recommendations. This enabled a visual representation of results and representative quotes for reporting of results.

Ethics Approval

Approval for this study was granted in May 2023 by the Human Research Ethics Office at the University of Western Australia (ET000217).

Results

Results showed the significant impact of suicide on staff and the lack of appropriate workplace response, and supported the efficacy of the new workplace postvention model and approach. Findings are presented together with example deidentified participant quotes reported by sector (government, not-for-profit [NFP], and commercial) and either interview participant number (P) or focus group type (see Table 1).

The Significant Impact of Suicide on Staff

All 54 staff had experienced at least one death of a client or colleague by suicide in the course of their work. The impacts of these deaths ranged from immediate shock and confusion to longer-term physical, emotional, and psychological symptoms of traumatic stress, including avoidance, heightened anxiety, and flashbacks.

"It interferes with your thoughts for a day or two and sometimes longer – with a suicide you think about what has led up to it and feel quite sad for the person. When you go back [to work] it all opens back up for you. When you write up the incident report it all comes back – the trauma."

(NFP, P2)

"We’ve had that happen where we’ve had staff have three or four [suicide bereavement funerals] in a week and they’re mentally and physically blown away. They are just like 'we can’t do another.'"

(Commercial, P11)

There was also a common acknowledgement of the long-term impacts on staff of working with populations vulnerable to suicide, particularly when client engagement with a service was short-term and crisis-driven.

"It’s relentless in that respect, it’s client after client and it’s the same, you know, anxiety and tensions… I think that can be very difficult, especially when they have a lot of these clients over the years… exposure to distress and suicide is quite prevalent."

NFP, P6

"Some of those jobs [client facing] can be soul-destroying because all you see is the negativity – and you never know the [longer-term client] outcomes."

(Government, P9)

Participants explained that the lack of postvention guidance in the workplace could create or reinforce feelings of isolation, doubt, confusion, fear, and questioning when responding to a loss in the course of their work. In some cases, these feelings were further amplified by workplace inquiry/after action review processes, which could cause further isolation (from peers in particular), feelings of shame, culpability, and delayed grief. When the loss was personal (i.e., outside the workplace), participants reported that there were no specific interventions or supports following bereavement by suicide, other than short-term bereavement leave and the option to access the Workplace Employee Assistance Program (EAP).

The impacts of suicide had a direct effect on work performance. There were instances of staff doubting their ability to continue to perform their roles. Others avoided the site of the suicide. Some staff were wary in situations like those in which the suicide had occurred. Many were frustrated or angry that the impact of suicide was unrecognized by their workplace and that they continued to have to carry these impacts alone and over a long period. Some staff had left the service and/or industry in which the suicide occurred.

"I know that a suicide led to a staff member leaving [the service] and [they] still avoid the place it happened."

NFP, P3

Funeral Arranger:

"The main causes for the suicidal stressors on [staff] are actually those organisational and operational stressors… compounded onto the traumatic stressors of the work."

Focus Group 1

The Lack of Appropriate Workplace Response

Only one of the workplaces in the sample had implemented a process to support staff following a suicide. With the exception of one of the workplaces which participated in the projects, none of the workplaces had provided postvention training to equip staff to support bereaved clients or colleagues after suicide. Some staff were offered an email or phone call. Others were provided a verbal debrief in which they were advised on the importance of self-care and the availability of EAP.

Referral to EAP was the most reported form of workplace response following suicide. Most participants reported that EAP was neither appropriate nor equipped to provide an effective response following suicide and said that they were more likely to seek support from a colleague with direct experience of the workplace and context.

"EAPs are not attuned [to] suicide…, they’re not actually able to tailor the support."

Government, P10

Where the death of a client or staff member occurred on a worksite, it was primarily dealt with as a critical incident with risk management processes enacted to determine staff and/or organizational responsibilities or liabilities. These risk management processes reportedly neglected to offer appropriate support for impacted staff, who described the priority as a return to normal service as soon as possible.

"At the time… [management said] 'this has happened, this is a lot – what do you need?' But very quickly it became about what the [clients] needed. And what we [staff] needed to do in terms of our responsibilities."

Government, P19

In some cases, critical incident investigations were reported to cause alienation and isolation for those who had been directly impacted by the death. Restrictions on conferring with colleagues during the investigation, for example, were described as contributing directly to the isolation of a staff member who died by suicide and to the suicidal ideation of the work health and safety staff responsible for their care. Most participants reported that organizational risk and reputation were prioritized over staff safety and support:

"On the Friday [they] had all the supports in place for safety but over the weekend things went bad and [they] took [their] life on the Sunday. I got back on the Monday and there was 2 days of me going 'I’m done, I’ve let this happen.' I want[ed] to talk to [their colleagues] and let them know that there is no way that they could have predicted this, but I couldn’t do that [because of the critical incident process]."

Focus Group 1

(Focus "If a [member of staff] commits suicide because of job-related issues, it’s a tragedy. It is. But it is nothing, nothing compared to if a [client] dies by suicide – [then] it’s 'who’s fault is this?' It is process driven [to] support to the [client] family."

Focus Group 1

Participants also noted that these deaths had not prompted workplace planning for how postvention responses should occur. Instead, they indicated that once the workplace had dealt with the incident in the context of compliance and risk management, it was considered over.

"There is so much to be done in the organisational and operational spheres, but that has to come from higher up with an understanding of how it really feels and works [for staff] on the floor. There is such a great sense of abandonment [for staff] [which increases the] risk of suicide."

Focus Group 1

The Efficacy of the Workplace Postvention Model and Approach

Participants reported that the projects were effective in engaging staff and managers in the design and implementation of a systemic approach to workplace postvention. The collaborative risk identification process, together with co-designed training, protocols, and supports, improved participant awareness, preparedness, and confidence with suicide postvention.

Project participants said that the time allocated by their workplace for the project was an acknowledgement of their roles, the impact of suicide, and the value of their work. They said that the postvention tools were effective because they responded directly to their context and needs.

"Having someone actually take an interest in what we have experienced, and [an] investment in looking at how we better manage those situations, [establish] clear processes has been exceptionally valuable."

NFP, P2

Project participants reported that having a clear postvention process in place made staff and management feel better prepared and would be helpful for the induction of new staff. They also emphasized the relevance of protective relationships with peers and colleagues and how these can be activated to maximize staff recovery following suicide.

"[We are] really excited with this [project] because [in the past] it’s been very much a case of reacting."

Quote SNFP, P13

"[The project] has been invaluable to our staff. Managing funerals brings with it an emotional load which is heightened in the case of suicide; as a result, staff retention is an industry challenge and programs like this have a significant impact in ensuring health & wellbeing for employees."

Commercial, P6

A range of implementation strategies were prompted through the projects, including role-playing scenarios, adding postvention to the agenda at team meetings, and integrating the self-care resources provided during individual supervision sessions.

Focus groups with participants from the broader sample (non-project participants) recommended a systemic approach to workplace postvention. Their suggestions included a structured workplace suicide response plan with clear steps, timeframes, and designated roles integrated with existing Work Health and Safety and/or Wellbeing strategies. They suggested workplaces provide training to better prepare staff for postvention and familiarize them with the postvention plan, and that interagency networks could support postvention responses and offer referral pathways. Each of these recommendations aligned with the focus of the new model (Clements, 2022) and approach taken in the projects.

Participants additionally recommended leadership and resourcing for strategies destigmatizing workplace culture and conversations about mental health and suicide. They suggested this could be further supported with the implementation of peer support programs to facilitate recovery following suicide.

"I’d like to see a better response higher up the line… to allow people to feel like there is support across the organisation."

Government, P10

Discussion

Findings revealed a clear tension between the prevalence of psychosocial risks and harms caused by staff exposure to suicide and the widespread lack of workplace response. There was evidence for a secondary negative impact of standard interventions such as referral to EAP and after action/critical incident review processes. Results supported the efficacy of the workplace postvention model and highlighted the need for targeted strategies to engage workplace leadership in a cultural change toward better support of staff exposed to suicide.

Because the impact of suicide is complex and variable, it is at odds with a workplace setting in which the common priority is a return to service. For this reason, other researchers have recommended a systemic approach to workplace postvention (Daniels et al., 2017; Spencer-Thomas & Stohlmann-Rainey, 2017), which is supported by findings of the current study.

In a systematic review of grief reactions, those bereaved by suicide reported higher levels of rejection, shame, stigma, need for concealing the cause of death, and self-blaming (Sveen & Walby, 2008). Causer et al. (2022) showed how these characteristics are refracted in the workplace setting. For example, the social silencing around suicide bereavement is evident in the implicit workplace expectation of a timely return to work following a death. The present study found that this silencing was also reflected in common workplace responses to suicide, i.e., referral to EAP and after action/critical reviews, which further reinforced feelings of isolation, shame, and rejection. These responses are associated with increased vulnerability to suicide (Andriessen et al., 2017).

The dissonance between the grief experiences of staff and the absence of workplace recognition and appropriate postvention creates further isolation and disenfranchisement. Disenfranchised grief is grief which is not publicly acknowledged or supported (Doka, 1989). This dynamic has been demonstrated in a series of studies. For example, emergency and health services staff report a reluctance to discuss the impacts of sudden or violent death and suicide because these conflict with the professional expectations of the role and workplace (Rudd & D’Andrea, 2015). Ambulance staff reported, "[a] lack of acknowledgment in the workplace that suicides may be traumatic and [offered] no guidance for staff on how to cope" (Nelson et al., 2020, p. 722). Psychologists described the serious personal and professional impacts of client suicide and "the need for more open communication, peer supports, space to grieve, as well as opportunities to engage in a learning process" (Finlayson & Simmonds, 2019, p. 18).

The present study found that rather than being prepared for and supported with the impact of suicide as part of a workplace system, staff were managing as individuals. A critical review of current workplace postvention practices (Causer et al., 2022) showed that the degree to which a workplace actively acknowledged, responded to, and supported staff following suicide was a mitigating factor in terms of staff outcomes. This was reinforced by findings of the current study.

Implications

Findings showed that the current lack of postvention preparedness placed staff at risk of a range of short- and long-term psychosocial harms. This creates a legislative and insurance risk for workplaces. The lack of postvention preparedness in workplaces may also have a negative impact on client and community outcomes, which would be a valid avenue for further research.

The new workplace postvention model effectively facilitated a shift from an individualized to a systemic postvention approach whereby training, governance, and support were designed with and for the workplace. Results also indicated that the approach improved awareness, preparedness, and confidence, which may go some way toward destigmatizing the experiences of suicide, as reported by participants.

Investigating the factors that empower staff working with suicide and suicide bereavement, along with exploration of leadership and implementation strategies, would be valuable avenues for further research.

Limitations

The small size of the study places limits on the generalizability of the findings. However, the prevalence of exposure to suicide, the negative experiences of staff, and the lack of workplace support or coordination were strikingly consistent across the sample. A larger study using a combination of qualitative and quantitative techniques would provide the opportunity to further explore the current state of workplace postvention and to test the model more widely.

Most of the sample were familiar with Neami National, and those from the four projects had engaged directly with Researcher Clements. This was managed during data collection through the participation of other researchers in interviews and focus groups and in the analysis through cross-checking of data relevance and categorization.

Conclusion

Staff exposure to suicide was widespread, and negative short- and long-term psychosocial impacts were prevalent. Workplaces had neither equipped staff to deliver postvention nor supported them with the impacts of suicide. Current workplace responses are ineffective and potentially harmful.

The new model of workplace postvention was effective in supporting workplaces with a systemic approach to suicide postvention. Findings showed the positive results of co-designing tailored workplace postvention (training, governance, and supports) according to organizational context, capacity, and need.

References

Andriessen, K. (2009). Can postvention be prevention? Crisis, 30(1), 43–47. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910.30.1.43

Andriessen, K., Krysinska, K., & Grad, O. T. (Eds.). (2017). Postvention in action: The international handbook of suicide bereavement support. Hogrefe. https://doi.org/10.1027/00493-000

Andriessen, K., Rahman, B., Draper, B., Dudley, M., & Mitchell, P. B. (2017). Prevalence of exposure to suicide: A meta-analysis of population-based studies. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 88, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.01.017

Australian Government Productivity Commission. (2020). Inquiry report – mental health. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/report

Bambridge, C., & McLean, M. (2023). State of the states in suicide prevention. https://www.suicidepreventionaust.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/State-of-the-States-Report-2023.pdf

Causer, H., Spiers, J., Efstathiou, N., Aston, S., Chew-Graham, C. A., Gopfert, A., Grayling, K., Maben, J., van Hove, M., & Riley, R. (2022). The impact of colleague suicide and the current state of postvention guidance for affected co-workers: A critical integrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, Article 11565. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811565

Cerel, J., Maple, M., van de Venne, J., Moore, M., Flaherty, C., & Brown, M. (2016). Exposure to suicide in the community: Prevalence and correlates in one U.S. state. Public Health Reports, 131(1), 100–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491613100116

Clements, A., Nicholas, A., Martin, K. E., & Young, S. (2022). Towards an evidence-based model of workplace postvention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), Article 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010142

Clements, A. M. R. (2022). A case study in workplace postvention with funeral staff [MPhil Dissertation]. University of Western Australia. https://api.research-repository.uwa.edu.au/ws/portalfiles/portal/189407645/THESIS_MASTER_BY_RESEARCH_CLEMENTS_Alison_Mary_Rose_2022.pdf

Daniels, K., Gedikli, C., Watson, D., Semkina, A., & Vaughn, O. (2017). Job design, employment practices and well-being: A systematic review of intervention studies. Ergonomics, 60(9), 1177–1196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2017.1303085

Doka, K. (1989). Disenfranchised grief: Recognizing hidden sorrow. Lexington Books.

Finlayson, M., & Simmonds, J. (2019). Workplace responses and psychologists’ needs following client suicide. OMEGA—Journal of Death and Dying, 79(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222817709693

Grad, O. (2005). Suicide survivorship: An unknown journey from loss to gain – from individual to global perspectives. In K. Hawton (Ed.), Prevention and treatment of suicidal behaviour: From science to practice (pp. 351–369). Oxford University Press.

Guest, G., Namey, E., Taylor, J., Eley, N., & McKenna, K. (2017). Comparing focus groups and individual interviews: Findings from a randomized study. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(6), 693–708. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2017.1281601

Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Molnar, B. E., Sprang, G., Killian, K. D., Gottfried, R., Emery, V., & Bride, B. E. (2017). Advancing science and practice for vicarious traumatization/secondary traumatic stress: A research agenda. Traumatology, 23(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000122

National Suicide Prevention Adviser. (2020). Connected and compassionate: Implementing a national whole of government approach to suicide prevention (final advice). https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/getmedia/543d313c-5749-404d-b349-b08db3a7fd96/Connected-and-Compassionate

Nelson, P. A., Cordingley, L., Kapur, N., Chew-Graham, C. A., Shaw, J., Smith, S., McGale, B., & McDonnell, S. (2020). ‘We’re the first port of call’ – Perspectives of ambulance staff on responding to deaths by suicide: A qualitative study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 722. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00722

Pirkis, J., Reavley, N., & Nicholas, A. (2019). Exposure to suicide in Australia: A representative random digit dial study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 259, 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.050

Pitman, A. L., Osborn, D. P., Rantell, K., & King, M. B. (2016). Bereavement by suicide as a risk factor for suicide attempt: A cross-sectional national UK-wide study of 3432 young bereaved adults. BMJ Open, 6(1), Article e009948. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009948

Rudd, R. A., & D’Andrea, L. M. (2015). Compassionate detachment: Managing professional stress while providing quality care to bereaved parents. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 30(3), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240.2014.999079

Spencer-Thomas, S., & Stohlmann-Rainey, J. (2017). Workplaces and the aftermath of suicide. In K. Andriessen, K. Krysinska, & O. Grad (Eds.), Postvention in action: The international handbook of suicide bereavement support (pp. 174–185). Hogrefe.

Sveen, C. A., & Walby, F. A. (2008). Suicide survivors’ mental health and grief reactions: A systematic review of controlled studies. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 38(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2008.38.1.13

The Australia Institute & Centre of Future Work, Carter, L., & Stanford, J. (2021). Investing in better mental health in Australian workplaces. The Australia Institute Centre for Future Work.

Work Health and Safety Act 2011. (2023). https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2011A00137/latest

History

Received March 22, 2024

Revision received October 27, 2024

Accepted November 11, 2024

Published online December 10, 2024

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the guidance of the Project Advisory Group: Karl Andriessen, The University of Melbourne; Sharon Bower, Suicide Prevention Australia; David Kelly, Zoot Training Consultants; Sharon McDonnell, Suicide Bereavement UK; Rachael McMahon, Australian Public Service Commission; and Darragh O’Keeffe, National Mental Health Commission.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Publication Ethics

Approval for this study was granted in May 2023 by the Human Research Ethics Office at the University of Western Australia (ET000217).

Funding

Sources of support: Neami National, Paul Ramsay Foundation.

ORCID

Karl Andriessen: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3107-1114

Alison Clements: alison.clements@uwa.edu.au